Humanity has no greater invention than writing. The history of humanity as a society begins at the moment when humans felt the need to express themselves and started searching for the best ways to communicate. On this path of discovery, the idea of writing was not merely a step forward or a leap but a monumental breakthrough. It elevated humans to divine beings who triumphed over the transient nature of time: through writing, humans managed to echo their words across generations indefinitely. "The written word endures forever" – this not only achieves personal immortality but also initiates the construction of a united, cohesive, and cultured society. Each generation feeds on the written heritage of the previous one while adding new contributions for the generations to come.

The immense importance of writing has been felt throughout history, either consciously or subconsciously, especially when the foundation of cultural, national, or state unity was being laid. Thus, it is no coincidence that Georgian historical sources link the creation of the Georgian script and the founding of the Georgian state to the same person, King Pharnavaz, in the 3rd century BCE. Modern scholars view this tradition critically, but it is impossible not to see a kernel of truth in it: uniting a fragmented tribal society into one nation is no easy task, and anyone undertaking this mission would undoubtedly consider the best means to achieve it. In this context, a national script is an indisputable leader: nothing can better enable people to communicate in a common language and accelerate the exchange of cultural ideas within society. Therefore, even if the Georgian script was not directly created by Pharnavaz, the idea of its creation, dissemination, or establishment must have emerged during his era.

But when exactly this idea became a reality, we do not know. Scholars provide entirely contradictory answers to this question. Researchers of the 19th and early 20th centuries speculated that the Georgian script was introduced before Christ. However, recent studies have not confirmed this hypothesis: the oldest securely dated inscriptions discovered so far belong to the 4th century CE. Many modern scholars believe that the Georgian script was likely created during the Christian era, possibly in the 2nd-3rd centuries CE, within a small Georgian Christian community.

The precise dating of the Georgian script's creation should be left to historians and archaeologists, relying on historical material. However, the primary historical source for the history of writing remains the script itself: the shapes of the letters and their calligraphy can tell us a great deal about their creator, their intentions, worldview, and artistic vision. To delve into this, let us examine the earliest form of the first Georgian script – Asomtavruli:

A mere glance at early Asomtavruli reveals an emphasis on order, regularity, and precision. All letters are of equal height and are constructed from geometric shapes – right angles, circles, and arcs. Every element of the letters is connected at right angles, and each letter itself is a geometric figure. No free or curved strokes are visible anywhere. In a word, everything is so regular that the perfect shapes of the letters could be drawn with a compass and ruler.

What might this mathematical precision of the Asomtavruli script signify? A survey of European, African, and Asian scripts reveals that Georgian is unique in this respect: while lines, circles, arcs, and other geometric shapes are present in other scripts, the consistent adherence to mathematical precision in all letters is unmatched. This strict observance of principles cannot be a coincidence.

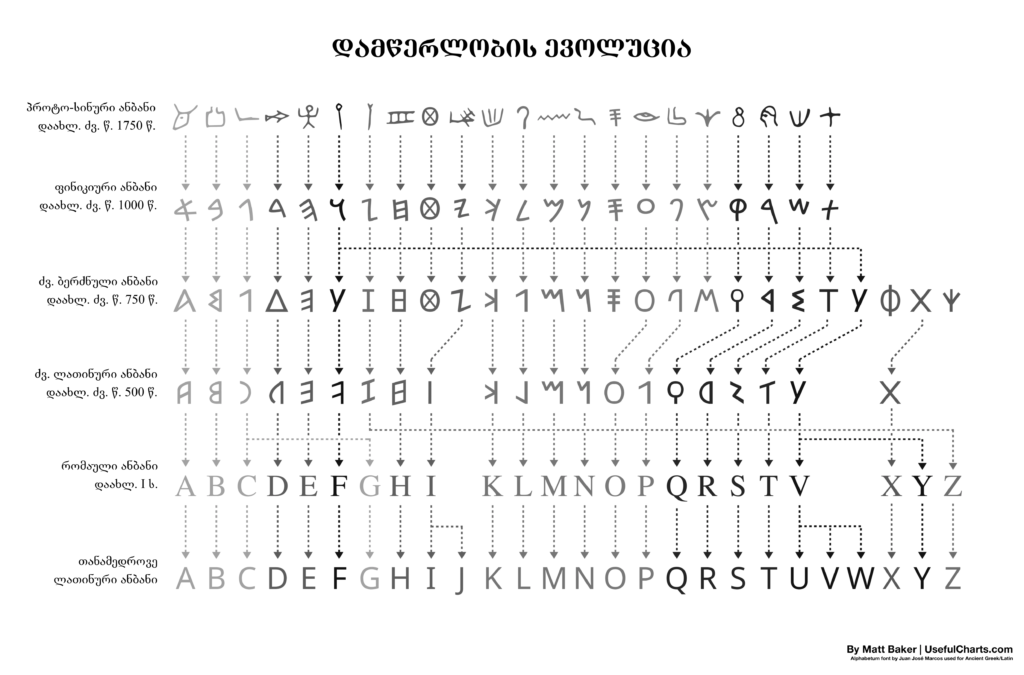

The fact that it cannot be coincidental means that Asomtavruli is the product of its creator's ingenuity, not a system derived or developed from another script. Interestingly, Georgian writing stands out in this regard as well. Almost all European scripts – Latin, Cyrillic, Gothic, Coptic – were derived from Greek writing, involving minor modifications or stylizations of letter shapes. In turn, the forms and names of Greek letters were borrowed from the Phoenician script. Aramaic, Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac scripts also evolved from Phoenician origins. All these scripts trace back to a single root form and develop along various evolutionary paths.

In such systems, strict geometric regularity is impossible because evolution, driven by rapid writing, produces free strokes and curved lines. The beauty of Greek, Arabic, or Syriac calligraphy is achieved through the harmonious arrangement of irregular curved lines, not through the mathematical precision of strict geometric shapes. Thus, the rigorous geometric nature of Asomtavruli indicates the deliberate and executed vision of its creator – an individual with profound intentions.

We do not know exactly who this individual was or when they lived, but their creation speaks for itself. There can be no doubt that this person was a state-minded individual with significant political goals. They were not only the creator of the Georgian script but also of Georgian literature and literacy. The creation of the Georgian script symbolizes the voice of the Georgian people to the world: "Hello, world!" From now on, the global cultural heritage includes the legacy of words expressed in the Georgian language, marking the birth of the Georgian nation in world history. Beyond saying hello to the world, the first words of the Georgian nation – its script – also conveyed who we are, where we are, and what we want. These declarations are clearly embedded in the geometric Asomtavruli script conceived in the mind of its creator.

First and foremost, the fact that the shapes of Georgian letters do not replicate the outlines of any other script but are instead products of the creator's mind, is a clear expression of striving for individuality and independence. During the era when the creation of the Georgian script is presumed, Georgia lay between two great cultures: the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) and Persia. Both empires possessed rich literary traditions; Latin and Greek scripts prevailed in one, while Aramaic and Pahlavi varieties dominated the other. Numerous Greek and Aramaic inscriptions found on Georgian territory demonstrate that these scripts were not foreign to the Georgian people. The kingdoms of Kartli and Colchis were culturally and politically closely connected to these two empires, often falling under the influence of one or the other. Against this backdrop, the most powerful means of expressing Georgian thought – the Georgian script – was created. It borrowed neither Byzantine nor Persian letter forms, instead inventing entirely new outlines. In that era, this was undoubtedly a political statement of cultural uniqueness.

Nevertheless, the Asomtavruli script leans more toward the West, Byzantium, and Christianity than toward the East. It is not difficult to observe that the initial letter of Christ, the Georgian letter Ⴕ "kani," in Asomtavruli takes the exact shape of the Christian cross. Some researchers believe that the letter Ⴟ "jani," which begins the word "cross" (ႿႥႠႰႨ, ჯვარი), results from the intersection of the initials of Jesus Christ (ႨႤႱႭ ႵႰႨႱႲႤ) and represents Christ's monogram.

It is difficult to dismiss these correspondences as mere coincidence. Furthermore, while the letter shapes are unique, the order of the Georgian alphabet closely mirrors the sequence of Greek letters. Even more intriguing is the fact that letters representing the same sound in Georgian and Greek have identical numerical values: the Georgian letters ႲႩႤ (325) correspond directly to the Greek ΤΚΕ (325). Scholars argue that such deliberate alignment was intended to simplify the translation of Greek texts into Georgian. Letters that represent sounds familiar to Greek but foreign to Georgian, such as ჱ, ჳ, and ჵ, were also introduced into the Georgian alphabet to facilitate transliteration of Greek names. Similarly, the letter combination ႭჃ, representing the Georgian sound "u," mirrors Greek usage. This does not contradict the nation’s pursuit of identity but rather clarifies its cultural, religious, and political stance. The message of the creator of Georgian literacy becomes even clearer: Georgian culture and statehood are both unique and integral to European Christian civilization. We aim to translate and adopt Christian literature while preserving our national identity. Later, King Vakhtang Gorgasali reiterated this sentiment in his will: "Do not abandon the path of the Greeks."

The choice of geometric figures as the forms of letters in Asomtavruli also reflects the goals and worldview of its creator. The creator sought perfection in form. For the architect of Asomtavruli, perfection lies in mathematical precision. The idea that the ideal world can be described through mathematical formulas and that all meaning resides in geometric shapes and numbers is not new. This concept was widely embraced in the philosophy of Neopythagoreans and Neoplatonists during the era when the Georgian script is thought to have emerged. Precision, perfection, and ideality are undoubtedly interconnected. Thus, the creator of Georgian writing aimed to grasp the essence of writing and implement its most perfect and absolutely precise version. For this creator, mathematics was the path to achieving this goal. Whether Asomtavruli is truly perfect may be debated, but its creator’s pursuit of perfection is undeniable. This characteristic is, inherently, the hallmark of a calligrapher: for them, writing is not merely lines representing sounds but ideal, perfect, beautiful, and exquisite lines. Thus, from its inception, the Georgian script has been determined by the pursuit of perfection and beauty, and Georgian calligraphers are destined to carry this aspiration forward.

During the early centuries of Christianity, as the newly Christianized peoples of Eastern Europe – Goths, Copts, Armenians, Caucasian Albanians, and Slavs – created national scripts to preach the Word of God and began literary endeavors in their native languages, each chose its own path. For some, the creation of a script signified more than just spreading Christianity. For the Goths, previously considered barbarians by the Greeks, it marked an entry into the Byzantine cultural sphere. For the Copts, descendants of the Egyptians, it represented a rejection of their national paganism and acceptance of a new, foreign religion. The primary message of Georgian writing, however, was this: "Hello world, we are here, Georgians, an independent nation with a unique culture, part of European Christian civilization, seeking perfection, precision, and beauty."

David Maisuradze

2022, Rustavi